This blog is written as response to the thinking activity on the topic of Feminist and Marxist criticism, given by Pro. Dilip Barad sir at the Department of English, MKBU.

Queer theory

Queer theory is a field that explores different forms of non-normative sexual identities and behaviors, including homosexuality, cross-dressing, bisexuality, and transsexuality. Originally, the term "queer" was used in a derogatory way to criticize same-sex love, but in the early 1990s, the LGBTQ+ community embraced it for self-identification and scholarly exploration.

Lesbian and gay studies emerged as liberation movements in the late 1960s and 1970s, advocating for equal rights during a period of social upheaval. Initially, these movements were somewhat separate, but over time, there has been a recognition of shared history and goals. In the 1970s, researchers focused on uncovering the works of nonheterosexual writers throughout history.

In the 1980s and 1990s, queer theorists challenged the idea of a fixed gay or lesbian identity. Drawing from poststructuralist thinkers like Derrida and Foucault, they questioned binary oppositions like male/female and heterosexual/homosexual. Adrienne Rich introduced the concept of a "lesbian continuum" to highlight the diverse spectrum of female relationships beyond just physical intimacy.

Later, theorists like Eve Sedgwick and Judith Butler critiqued the normativity of heterosexuality and deconstructed the assumption of stable sexual identities. They argued that categories like heterosexual and homosexual are cultural constructs rather than universal, transhistorical types. Michel Foucault's work, especially in "History of Sexuality," influenced this perspective.

Judith Butler, in "Gender Trouble," proposed the idea that gender and sexuality are performative, meaning cultural discourse shapes these categories and the individual then enacts them. Queer reading became a way to challenge established cultural boundaries.

Debates within queer theory include the tension between radical constructionism, which sees identities as linguistic products specific to a culture, and the need to affirm enduring human identities for political action. Many journals, conferences, and academic programs are now dedicated to queer theory and LGBTQ+ studies.

Various anthologies and books cover queer theory, including works by Karla Jay, Joanne Glasgow, Diana Fuss, and others. The field continues to grow with contributions from scholars exploring the intersections of race, class, and gender in the construction of identities.

Dynamics of Lesbian and Gay Literary Criticism

Lesbian and gay literary theory emerged prominently in the 1990s as a distinct academic field. Unlike earlier literary theory works, which largely overlooked lesbian and gay studies, this field gained recognition with dedicated sections in bookstores, academic programs, and courses like 'Sexual Dissidence and Cultural Change' at the University of Sussex.

This interdisciplinary field, influenced mainly by cultural studies, goes beyond exclusive interest for gays and lesbians. It shares similarities with feminist criticism in its social and political aims, resisting homophobia, heterosexism, and challenging the privileging of heterosexual norms.

However, lesbian and gay criticism is not a monolithic entity. Two main strands within lesbian theory include lesbian feminism and libertarian lesbianism. Lesbian feminism, rooted in the 1980s feminist context, emphasizes the intersection of lesbianism with feminist ideals. It critiques mainstream feminism for neglecting issues of race, class, and sexual orientation, introducing the concept of the "lesbian continuum" to highlight a broad spectrum of woman-identified experiences.

In the 1990s, lesbian criticism evolved within the framework of "queer theory," aligning with the interests of gay men and rejecting fixed categories. Queer theory challenges traditional binary oppositions, especially the heterosexual/homosexual dichotomy. Drawing on post-structuralist ideas, it questions the stability of identity categories, critiquing the notion of fixed essences.

Significantly, queer theory opposes essentialism, suggesting that sexual identity is not a stable and inherent characteristic but rather a performative construct shaped by social and cultural influences. This approach has both political and literary implications, encouraging a reevaluation of traditional realism in literature and favoring texts that subvert conventional structures.

The field of lesbian and gay criticism continues to evolve with new perspectives and critiques. Its rejection of essentialism and embrace of anti-realist elements in literature are notable features. Ultimately, lesbian and gay criticism seeks to bring visibility to diverse sexual orientations, challenge societal norms, and contribute to a more inclusive understanding of literature and culture.

What the Lesbian/gay critics do:

Identify influential LGBTQ+ writers, especially from the twentieth century.

Identify and discuss explicit LGBTQ+ moments in mainstream literature, avoiding vague interpretations.

Use metaphors to depict LGBTQ+ experiences as moments of crossing boundaries, reflecting conscious resistance.

Expose homophobia in mainstream literature, criticizing omissions and biases in discussing LGBTQ+ aspects.

Bring attention to previously unnoticed homosexual elements in mainstream works, like the homoerotic tenderness in First World War poetry.

Focus on forgotten literary genres shaping gender ideals, such as nineteenth-century adventure stories with a British 'Empire' setting.

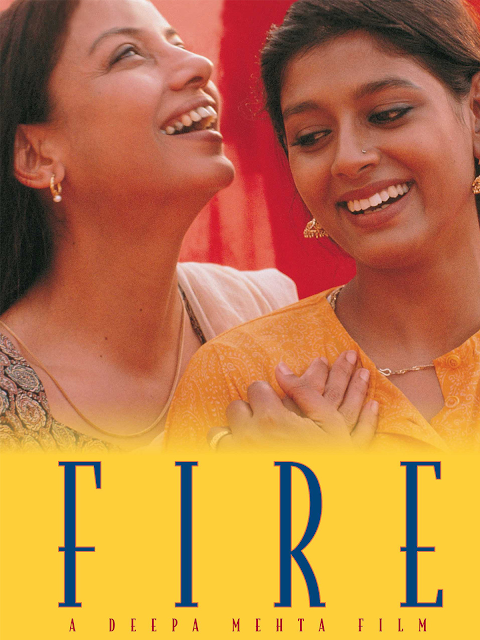

With the example of film “Fire”(1996)

"Fire," a film directed by Deepa Mehta, stands out as a groundbreaking work in Indian cinema for its exploration of LGBTQ+ themes. Mehta, considered a trailblazer in the Indian context, contributes significantly to the canon of creators addressing these themes in a country where such discussions have been traditionally limited.

Within the narrative of "Fire," the relationship between Radha and Sita, two sisters-in-law, serves as the focal point for exploring same-sex experiences within a conservative Indian society. Mehta's choice to highlight these experiences underscores a deliberate effort to shed light on often marginalized narratives, challenging the prevalent norms of storytelling centered around heterosexual relationships.

Metaphorically, "Fire" reflects broader societal struggles faced by LGBTQ+ individuals. Radha and Sita's story becomes a metaphor for the conscious resistance against established norms and the challenges of self-identification within a society that may not readily accept diverse sexual orientations.

However, the film itself faced significant backlash in India, revealing the deep-seated homophobia within mainstream cinema and society. The controversy surrounding "Fire" provides a lens through which to critique the reception of LGBTQ+ themes in Indian cinema and underscores the film's role in challenging societal biases.

"Fire" courageously foregrounds homosexual aspects within its narrative, explicitly depicting the relationship between Radha and Sita. This bold approach positions the film as a noteworthy cinematic endeavour that consciously brings to the forefront the realities of LGBTQ+ relationships within the broader landscape of Indian cinema.

"Fire" can be seen as a genre-defying piece within Bollywood, challenging conventional storytelling norms. Mehta's film disrupts established ideas about femininity, marriage, and sexuality in Indian cinema, contributing to a more inclusive representation and understanding of diverse sexual orientations.

"Fire" and its critical analysis exemplify the multifaceted efforts to establish LGBTQ+ narratives and creators within the canon of Indian cinema, marking a significant step toward fostering inclusivity and breaking away from traditional storytelling norms.

Ecocriticism

Ecocriticism emerged in the late 1970s by combining "criticism" with a shortened form of "ecology." It explores the connections between literature and the environment, considering the impact of human activities on nature. The focus is on representations of the natural world in literature.

From early biblical accounts to pastoral themes in Greek and Roman literature, nature has been a recurring theme. In the 18th century, Gilbert White's "Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne" initiated nature writing in England, while in America, William Bertram's "Travels through the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida" continued this trend. In the 20th century, influential books like Aldo Leopold's "A Sand County Almanac" and Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring" drew attention to environmental degradation. As ecological concerns grew, ecocriticism emerged in the 1990s, becoming a recognized field of literary study.

Ecocritics analyze literature through various perspectives, addressing issues such as anthropocentrism (human-centered views) and the interconnectedness of human culture and nature. They encourage "green reading" across literary genres, including nature writing by authors like Thomas Hardy and Mark Twain. Ecofeminism examines how male-authored literature portrays women's roles in natural fantasies. There's also a growing interest in non-Western cultures, such as Native American oral traditions, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all living things.

While some argue for a shift to ecocentric religions, others believe reform lies in recognizing human responsibility and stewardship. Despite differences, ecocritics agree that literature, fueled by imagination and emotion, plays a crucial role in complementing scientific knowledge to address ecological challenges.

Ecocriticism or green studies?

Ecocriticism, also known as green studies, is essentially the examination of the relationship between literature and the natural environment. Coined in the late 1970s, the terms "ecocriticism" and "green studies" are used interchangeably to describe this critical approach that gained prominence in the late 1980s in the USA and the early 1990s in the UK.

In the USA, Cheryll Glotfelty is recognized as a key figure, co-editing "The Ecocriticism Reader" in 1996 and co-founding the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) in 1992. This signaled the emergence of ecocriticism as an academic movement, with its own journal, Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment (ISLE), starting in 1993.

The term "ecocriticism" originated in the late 1970s during meetings of the Western Literature Association, tracing back to William Rueckert's 1978 essay. Cheryll Glotfelty later revived and popularized it at the 1989 WLA conference. In the USA, ecocriticism draws inspiration from transcendentalist writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau, celebrating nature, life force, and wilderness in America.

In the UK the ecocriticism, or green studies, looks to British Romanticism of the 1790s. Jonathan Bate, author of "Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition," is a prominent figure in British ecocriticism. While the USA emphasizes celebration, the UK approach tends to be more cautionary, warning against environmental threats from various forces.Ecocriticism is more established in the USA, with ASLE and ISLE, while the UK is still developing its infrastructure. Both variants share the goal of exploring the intersection of literature and the environment but differ in emphasis and tone, with the American approach often celebratory and the British approach more cautionary. The existence of these national variants mirrors the distinctions seen in cultural materialism and new historicism.

Culture and nature

Ecocriticism challenges the prevailing notion in literary theory that everything is socially and linguistically constructed. Unlike many other theoretical frameworks, ecocritics assert that nature exists independently of human interpretation and isn't merely a cultural concept. This rejection of constructedness is a significant departure from the broader theoretical orthodoxy that views the external world as socially and linguistically constructed.

Ecocriticism questions the idea that everything, including nature, is textualized into discourse. Kate Soper, in her book "What is Nature?" dismisses the notion that language has a role in causing the hole in the ozone layer. The movement critiques the foundational belief in constructedness, which is a key aspect of literary theory.

However, it's crucial to note that ecocritics don't hold a naive, pre-theoretical view of nature. There have been intense debates within ecocriticism regarding the understanding of nature. For instance, American Wordsworth critic Alan Liu contends that calling something 'nature' and seeing it as 'simply given' can be a way of avoiding the politics that shaped it. Liu's position suggests that 'nature' might be an anthropomorphic construct created for specific purposes.

The debate on the constructedness of nature is evident in the confrontation between Liu and various ecocritics like Jonathan Bate, Karl Kroeber, and Terry Gifford. Liu's argument that 'there is no nature' has sparked discussions and stimulated the definition of ecocritical positions. The meaning of the word 'nature' is a significant point of contention in ecocriticism, echoing the debates found in other theoretical frameworks.

The social and linguistic constructedness of reality, also known as 'the problem of the real,' is a key issue that ecocriticism brings to the forefront. While attitudes toward nature may vary culturally, ecocritics emphasize the need to distinguish between figurative and literal truth. The movement prompts a clarification of thoughts on this issue.

Ecocriticism also raises questions about distinctions and their clarity. The distinction between nature and culture, though not always absolute and clear-cut, remains essential. The existence of intermediate states does not undermine fundamental distinctions. Ecocritics argue that recognizing the shades of grey doesn't negate the black-and-white difference between nature and culture.

The discussion extends to environmental areas, moving from 'the wilderness' to 'the domestic picturesque.' These areas represent a spectrum from predominantly 'pure' nature to predominantly 'culture.' Despite uncertainties about the positioning of specific elements, ecocritics maintain the importance of the fundamental distinction between nature and culture.

Ecocritics argue that even if nature writing often focuses on areas with a blend of culture and nature, it doesn't negate the existence of nature. The movement highlights the special function that wilderness areas serve for humanity, emphasizing the need to preserve such spaces, even as global warming and other anthropocentric problems impact every region on the planet.

Ultimately, ecocriticism encourages a broadened perspective in literary and critical studies, urging scholars to consider ecological concerns alongside traditional issues of gender, race, and class. The movement suggests that addressing environmental issues is a prerequisite for addressing other social injustices.

What Ecocritics do

Ecocritics re-examine classic literary works through an ecocentric lens, focusing on the portrayal of the natural world.

They broaden the application of ecocentric concepts, utilizing them beyond nature, including ideas of growth, energy, balance, imbalance, symbiosis, mutuality, and sustainable resource use.

Ecocritics emphasize canonical authors who prominently feature nature in their works, such as American transcendentalists, British Romantics, John Clare, Thomas Hardy, and early 20th-century Georgian poets.

They expand literary-critical approaches by highlighting "factual" writing, particularly reflective topographical pieces like essays, travel narratives, memoirs, and regional literature.

Ecocritics move away from social constructivism and linguistic determinism prevalent in dominant literary theories, shifting focus to ecocentric values like keen observation, collective ethical responsibility, and acknowledging the significance of the external world.

Example of ecocriticism through poem 'In Time of "The Breaking of Nations."

I

Only a man harrowing clods

In a slow silent walk

With an old horse that stumbles and nods

Half asleep as they stalk.

II

Only thin smoke without flame

From the heaps of couch-grass;

Yet this will go onward the same

Though Dynasties pass.

III

Yonder a maid and her wight

Come whispering by:

War's annals will cloud into night

Ere their story die.

In 1915, amid the tumult of the Great War, Thomas Hardy penned the poignant poem 'In Time of "The Breaking of Nations."' The verses grapple with the shattering of civilizations and the desperate quest for enduring elements amidst the chaos. Hardy's chosen symbol of permanence is the humble ploughman, a figure engaged in low-tech agriculture—a man harrowing clods in a slow, silent walk with an old horse. However, it's crucial to note that while the poem was transcribed in 1915, the inspiration for the timeless ploughman dates back to Hardy's observation in 1870.

From an ecological standpoint, Hardy's personal past becomes a metaphorical landscape where the seed of an idea is planted, matures, and is eventually recycled to meet a future need. The gestation of the poem mirrors the patient processes of growth and cultivation depicted within it. The poet's autobiographical reflections reveal that the ploughman sighting occurred during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, a day marked by the bloody battle of Gravelotte. Despite the myriad changes over the intervening years, Hardy clung to the belief in the permanence and timelessness of the natural world.

The poem's narrative unfolds as the leisured speaker/observer stands between two ecological areas: the rectory garden symbolizing horticulture, and the valley of arable land representing agriculture. The couple beyond the garden—maid and wight—exemplify a slow, silent, and harmonious existence. However, the negative image of thin smoke without flame, emanating from burning grass heaps, disrupts the vision of united, productive harmony. This burning symbolizes the destructive human activity that threatens the symbiosis between agriculture and horticulture, a metaphor for the entropic carnage of war.

In seeking solace during wartime, the poet turns not to Tennyson's verses but to the world around him, finding comfort in the figure of the ploughman. From a contemporary perspective, the confidence restored by contemplating this 'timeless' figure may seem overly optimistic. Hardy's emblem of immutability becomes an emblem of fragility in our era, highlighting the precariousness of the ecological balance.

Characteristics of this ecocentric reading include an awareness of the poem's growth processes, diverse materials contributing to its development, identification of explicitly ecological content, retroactive irony, and an eclectic approach. Ecocriticism, as embodied in this analysis, is a diverse and open biosphere, echoing Walt Whitman's proclamation: 'I am large, I contain multitudes.'

No comments:

Post a Comment